Last month, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit heard oral arguments in Carrol Shelby Licensing, Inc. v. Halicki, Case No. 23-3731. It is an appeal after a trial victory for defendants, secured by, inter alia, MWM partner Anton (Tony) N. Handal, and defended on appeal by MWM partner Marina V. Bogorad. It is also a culmination of more than twenty years of copyright litigation over an alleged car character featured in a 2000 blockbuster film called “Gone in Sixty Seconds,” starring Nicolas Cage and Angelina Jolie.

The film is a remake of a 1974 movie of the same name. The basic story is that a group of thieves needs to steal a lot of cars in a short amount of time. They assign female code names to each car to keep track of them. One car is termed Eleanor. The thieves end up stealing the original Eleanor multiple times. The original Eleanor looks like this:

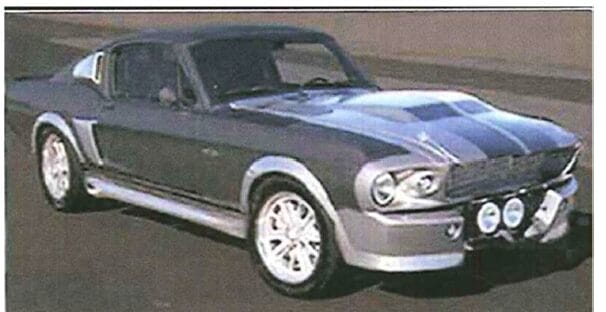

In the 2000 version, Eleanor looks like this:

Defendants in this litigation at some point made replica 2000 Eleanors. Accordingly, the central question came to be: is Eleanor a copyrightable character?

The question of character’s copyrightability that is separate from the copyright of the underlying story has troubled courts for years. The seminal decision on the issue dates back to the 1930s, when one of the most famous jurists, Judge Learned Hand, grappled with it in Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp., 45 F.2d 119, 121 (2d Cir. 1930).[1] The case dealt with characters from the play “Abie’s Irish Rose” and whether its characters were improperly used by a motion picture “The Cohens and The Kellys.” The rule that Nichols established is that generic and indistinctive characters cannot be protected apart from the underlying story. As an example, Judge Hand pointed to characters from William Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” and observed that they would not be protected to the extent they presented nothing more than “a riotous knight who kept wassail to the discomfort of the household, or a vain and foppish steward who became amorous of his mistress.”[2]

As the law evolved, copyrightability of characters remained an exception, not the rule. Characters, just like other forms of authorship in which an author’s originality is difficult to define, and whose expression is inherently abstract, must encounter a more rigorous copyrightability regime because this is the balance that the Constitution strikes.[3] That constitutional balance protects the public domain, which copyright law was designed to foster.[4]

Moreover, while under the 1909 Copyright Act, in force until 1979, a fictional character might have achieved copyright protection as a “component part” of a work, 17 U.S.C. §3 (1976), the statute changed in 1976. In the new statute, Congress did away with separate copyright protection for components of works. Under current law, copyright protection extends only to “original works of authorship” that are “fixed” in a “tangible medium of expression.” 17 U.S.C. §102(a).[5]

In fact, Congress specifically rejected proposals for characters’ categorical protection when considered apart from the work in which they appear, deeming it “unnecessary and misleading,” especially given that “the large majority” of characters are undeserving of copyright protection anyway.[6] Left to the courts, the test for character copyrightability now varies across the country.

In the Ninth Circuit, “not every comic book, television, or motion picture character is entitled to copyright protection.”[7] To qualify for the exceptional case of character copyrightability, a character must: (1) have “physical as well as conceptual qualities,” (2) be “sufficiently delineated to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears” and “display[] consistent, identifiable character traits and attributes,” and (3) be “especially distinctive” and “contain[] some unique elements of expression.”[8]

In Towle, the Ninth Circuit confirmed that the Batmobile meets this test.[9] In a colorful opinion that plays on familiar staples (such as “Holy copyright law, Batman!” and “To the Batmobile!”), the court held that the Batmobile’s “bat-like appearance has been a consistent theme throughout” all the works, and it is always “a crime-fighting car with sleek and powerful characteristics that allow Batman to maneuver quickly while he fights villains.” Importantly, the only time the Batmobile changes its distinctive appearance is when its traits require those changes to “adapt to new situations[.]”

By contrast, in Daniels, where the court dealt with characters from the animated picture “Inside Out” that plaintiff claimed were taken from her stories featuring color-coded emotions called The Moodsters, the latter failed the test because “[u]nlike …the Batmobile, which maintained distinct physical and conceptual qualities since its first appearance …, the physical appearance of The Moodsters changed significantly over time.”[10] Moreover, aside from the unprotectable association of colors with emotions, there were “few other” consistent traits “over the[ir] various iterations.”

So what about Eleanor? As defendants argued, Eleanor wants to be the Batmobile but fails to live up to its distinctiveness and consistency. The 2000 Eleanor looks nothing like the original. While plaintiff in the “Gone in Sixty Seconds” litigation claimed that Eleanor is always hard to steal and wins in every chase, these claimed traits are not always there—and, in any event, are common to any car in a car heist movie. To borrow Judge Posner’s turn of phrase, these are “standard expressions, like language itself, without which the would-be author of a [car heist movie] … would be speechless.”[11]

In other words, Eleanor is no Batmobile but rather is a stock character common to its genre. While the trial court agreed with this assessment,[12] the Ninth Circuit is yet to speak on the subject. Stay tuned for more Eleanor news.

[1] See also Clancy v. Jack Ryan Enters., Ltd., 2021 WL 488683, at *38 (D. Md. Feb. 10, 2021) (“The controlling principle for character protection has emerged from Judge Learned Hand’s opinion in Nichols….”).

[2] Nichols, 45 F.2d at 121.

[3] See, e.g., Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 346-50 (1991) (copyright restrictions are constitutional touchstones).

[4] See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8 (Congress may provide copyright protection to “promote the Progress of Science”).

[5] See 1 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright, §2.12[A][1] (2024) (“The Register of Copyrights hit the nail on the head, explaining why ‘fictional characters’ are not separately identified as copyrightable works under the current Act.”); Daniels v. Walt Disney Co., 958 F.3d 767, 771 (9th Cir. 2020) (“[C]haracters are not an enumerated copyrightable subject matter under the [current] Copyright Act ….” (citing 17 U.S.C. § 102(a))).

[6] See U.S. Copyright Office, Supplementary Register’s Report on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law (H. Comm. Print, 89th Cong., May 1965), at p. 14, available at https://www.ipmall.info/sites/default/files/hosted_resources/lipa/copyrights/Supplementary%20Register%27s%20Report%20on%20the%20General%20Revision%20of.pdf.

[7] Daniels, 958 F.3d at 771 (citing DC Comics v. Towle, 802 F.3d 1012, 1019 (9th Cir. 2015)); see also Gallagher v. Lions Gate Ent. Inc., 2015 WL 12481504, at *7 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 11, 2015) (“Seldom are characters in copyrighted works afforded their own copyright protection outside of the works they are found in[.]”).

[8] Daniels, 958 F.3d at 771.

[9] 802 F.3d at 1019.

[10] 958 F.3d at 772.

[11] Bucklew v. Hawkins, Ash, Baptie & Co., LLP., 329 F.3d 923, 930 (7th Cir. 2003).

[12] Carroll Shelby Licensing, Inc. v. Halicki, 643 F. Supp. 3d 1048 (C.D. Cal. 2022).